Raja Rama Varma 1914-1931 ( The Raja who died at Madras )

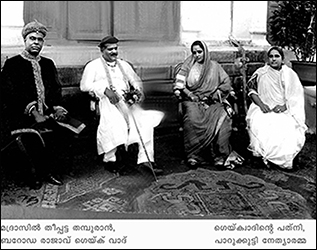

He was born in 1858. Mother was Kavu Thampuran and father Pana Namboodiripad. He was well versed in Ayurveda and Visha Vaidyam. Spoke excellent English. He was very good with finances and had great management skills. He married Parukutty Amma of the Kuruppath Tharawad, though as tradition demanded she was known as his consort. In the picture at the extreme right; The Raja is seated on the left, followed by Maha Raja Gaekwad of Baroda and his wife; with Parukutty Nethiarama at the right end.

G.T. Mackenzie, British Resident in Travancore and Cochin, in December of 1901 wrote to Mr. Winch in Government of Madras “the Elia Raja, the immediate heir, is a man of good physique and of some force of character. He is very frugal and lends his money out at interest.” Mr. Rajagopalachari, the Dewan of Cochin wrote in his memorandum dated 26th January 1900, giving great credit to the Elaya Raja for efficient management of the Amma Raja’s properties. Amma Raja’s properties or the Valiyamma Thampuran Kovilakam Estate was being managed by the Raja ever since he became the first Prince.

According to Sir T. Vijayaraghavachari, the Dewan, “His Highness conveys his commands in a Socratic method. You have to watch his words carefully not to miss the meaning. …..His Highness is a student of Spencer. At times, he would make me suspect he was an agnostic at heart. The act of worshipping in the temple, once H.H remarked to me”- ‘has a tonic effect. The spectacular side of the temples here has to be developed so as to leave a marked impression on those who go to the temples.’

(Herbert Spencer 1820-1903 was an English Philosopher.)

Report on the Administration of Cochin 1915-17 indicated that a public meeting to respectfully congratulate His Highness the new Raja was held on 11/1/1915. Installation ceremony took place ten days later followed by a Government garden party. The chief event of the year 1916 was the visit of His Highness the Raja to Delhi and Northern India. He left Ernakulam on the 8th October and returned to Ernakulam on the 29th November 1916. As reply to the welcome address given by the Mahajana Sabha of Cochin, he said : “ This tour has provided an opportunity for acquiring fresh information and new outlook in regard to many matters of administration and industrial concern, which, I trust, will not be entirely without fruits. It is my earnest desire to associate my people in an increasing measure with the Government of the State.” His Highness went to Coonoor to escape the hot summer, but had to return to the capital, due to the demise of the Senior Rani to participate in the ceremonies

.

T.K. Krishna Menon gave more details about this Raja’s period in his book ‘The Days that were’. ‘The next ruler was a great constitutional Monarch. His generous nature and lofty patriotism and desire to take the country through reasoned progress to the front place among the Indian States were visible in every act of his. He had ‘a dislike for all pomp and ostentatious display’. His knowledge of the Ayurvedic system of medicine and his special aptitude in the treatment of cases of poisoning were always at the disposal of the public. He evinced a parental solicitude in the elevation of the depressed and backward classes. The very first thing that engaged his attention was the financial position of the State……The result was remarkable. The annual income rose from 46 lakhs of rupees in 1914-8-15 to 86 lakhs in 1927-7-28 and a surplus from 12 to about 70 lakhs.’

Several Dewans served under His Highness the Raja. J.W.Bhore, B.A., I.C.S. was the first. He was consumed with the scheme he had envisioned to save the Forest tramway originated by the previous Raja, but was incurring losses. The Raja wanted to ditch the whole system. A handwritten letter by the Raja dated 11th May 1918 to Mr. Braidwood the British Resident more or less indicates his desire to replace Mr. Bhore.

Dewan Vijayaraghavachari replaced Bhore and was at the helm during the events of outbreak of Plague in Mattanchery, scarcity of rice in the State and riots in Trichur. To tackle the rice problem, he fixed maximum selling prices of local paddy and rice, opened a circar depot for sale to the poor and tried to procure Burma rice from Madras. In addition, he opened relief works to give labor to the unemployed and at Trichur opened a trial poor house to give kanji. Dewan’s preemptory order to put down the rioters in Trichur did not win approval of the Highness. As regards to Cochin Harbor, hydroelectric scheme, and paper pulp industry Dewan was non-conclusive for the time being. He co-operated with the start of boy-scouting in a quasi-Governmental mode. He favored progressivity of the legislative council. In spite of the laudable services of the Dewan there was a falling off and Dewan Narayana Menon replaced Vijayaraghavachari.

The three year tenure of Narayana Menon as Dewan was largely uneventful except for the heated activities in the legislative Council as regards to the Cochin Harbor scheme. Extract from Dewan Narayana Menon’s letter dated November 1924 was note-worthy “Keeping me on for another year does not commend itself to the consort and she wants to let me go at the end of my term and put in Narayana Iyer instead.”…… “On account of the condition of H.H’s health the administrative machinery has I fear gone out of order.”

On 6th December 1924, C.W.E. Cotton the Resident wrote to His Highness “Having regard to the state of your Highness’s health, you may perhaps wish to avail yourself for further term of Mr. Narayana Menon’s experience and the fact that he is so doughty a champion of the Durbar’s interest in the problems connected with the Cochin harbor scheme will make him difficult to replace until they are settled.”

Confidential letter from Hill Palace, Tripunithura, 14th December 24 to Mr. Cotton indicated “I propose to appoint Rao Bahadur Mr. T.S. Narayana Iyer’ my present Chief Judge to succeed Mr. Narayana Menon. I am glad to say that I am rapidly improving in my general health and there is less difficulty in walking.”

On 5th February 1925, Resident Cotton wrote to Patterson the officiating Secretary of the Government of India, Political Department. “Mr. Narayana Iyer is not a flyer and has no recent administrative experience. But his reputation is good, and if the selection is restricted to the officials in State Service, he is certainly the best man available. Narayana Menon was too steadfast a guardian of the State finances ‘to be no longer acceptable to the Maharaja’s consort who is the defacto ruler of the State. It is to be presumed that she has hopes that Mr. Narayana Iyer will prove more accommodating. The Maharaja is too old and too feeble to take any real active interest in the administration and the Dewan has to be constantly on his guard to prevent undue interference on the part of the consort whose ruling passion is the acquisition of wealth for her already wealthy family.”

T.K.Krishna Menon adds “But, as for Narayana Iyer, he had no hint of any extraordinary gifts. His conspicuous gift was negative. It was his silence. Events always played the trump card for him. His luck was a legend, and he was loyal to the last breath of his life.”

Narayana Iyer’s tenure as Dewan continued to be troublesome. Discontentment among the junior male Thampurans progressed to such an extent that a memorandum of no confidence against the administration was submitted to the Resident and the Secretary to the Madras Government. The Dewan had to defend the Raja who was for all purposes seemed to be out of the loop. British also was confronted with the vexing problem of how to deal with a mentally disabled ruler of a feudatory State.

The Junior Thampurans of the Ruling Family, Cochin wrote a letter to Lt, Col. C.G. Crosthwaite C.B.E., Agent to Governor General, Madras State on 10th October 1928. They requested an interview to discuss several troubling issues informally. Such an interview did take place and Dewan Narayana Iyer who was also present tried to rebut all the issues vigorously. Several letters were written by the Dewan, Crosthwaite and Kerala Varma the leader of the Junior Thampurans.

Narayana Iyer’s term was to end and frantic effort was made to replace him with the son-in-law of the consort/Raja. A few letters are available to substantiate this. However at this point the British authorities decided to bring in C.G. Herbert I.A.S. as Dewan

Lt. Colonel. H.R.N. Pritchard C.I.E., C.B.E. followed Crosthwaite as Agent to the Governor General, Madras State Agency. The interchange of letters that took place between Herbert and Pritchard certainly give a perspective of what happened between 1924 and 1932.

Herbert’s letter to Pritchard dated 24th December 1931 can be summarized as follows. 1. A note is enclosed in the letter to explain the difficulties experienced in the State of Cochin.

2. Intervention in the administration, might take two forms, one consisting of the transfer of the Sarvadhikariakar through whom the consort is effecting her influence and the second consisting of the appointment of Elaya Raja as Regent. The third possibility is to do nothing until the Raja dies or situation becomes so bad that the Government of India can take over.

The note written by Mr. Herbert has been so informal that liberal amount of paraphrasing has been resorted to. “It has been evident to me since I became Dewan rather more than a year ago that His Highness, owing to his age and ill-health, is incapable of taking any personal part in the administration. Under the constitution however many of the affairs of the State can only be transacted under the orders of the Maharaja or with his concurrence, and in spite of the present Maharaja’s incapacity orders continue to issue in his name. Obviously therefore, in fact, these orders are passed on His Highness’s behalf by others who have taken His Highness’s place in the administration.”

Herbert expands on the various courses he could take in such a dicey situation. “a change seemed very desirable, if not absolutely necessary, in the interest of the Thampurans – the members of the Ruling Family – for reasons which will be stated later.”

“For these reasons I discarded the idea of waiting till the situation reached a crisis before taking steps to improve it, and decided to adopt the alternative course of replacing the present Sarvadhikariakar by a man in whose integrity confidence may be reposed.” Herbert wanted to appoint the Sarvadhikariakar Mr. Narayana Pisharoti as the Commissioner of Devaswoms with the same pay grade and bring in Mr.Subramania Aiyer as the new Sarvadhikariakar. Herbert’s recommendations were questioned or rejected.

Herbert continues in the note “Earlier in this note I referred to the desirability of transferring the present Sarvadhikariakar in the interest of the Thampurans as the members of the Ruling Family are known. I will now examine this question in

some detail. Sometime ago now a deputation of these Thampurans made certain representations to Colonel Crosthwaite who was then Agent to the Governor General. Two of these representations related to the management of the Palliyara Muthalpidi Properties and the Valia Ammaraja’s estate. It may perhaps at this point be desirable to give a short explanation of these properties and the method of their management and to explain briefly the system of inheritance followed by the Cochin Ruling Family.

The Ruling Family follows the Marumakkathayam law and inheritance and is traced through the female line. Under this system of law the children belong not to their father’ but to the mother’s family and neither they nor their mothers are entitled to share in their father’s family property. This must be remembered in considering the Thampurans’ complaints.

Both the Ammaraja’s estate and Palliyara Muthalpidi properties appears to have been founded by a Raja who died in the Malayalam month of Edavam 1018 (88years ago). This Raja before he ascended the Musnad had acquired considerable private property which he increased during his reign. Before he died he gave property worth two lakhs to the female members of the family thus constituting the Ammaraja’s estate. The remainder of his properties he constituted as a separate estate for the male Thampurans and thus originated the Palliyara Muthalpidi properties. These properties have always remained under the direct management of the Ruler and it was the custom for the new Raja when he ascended the Musnad to add his private properties to the estate. His Highness the present Maharaja did not however do so. The properties may therefore either be regarded as family properties their management being vested in the Ruler for the time being in his capacity of Karanavan or head of the family: or, perhaps less probably, as Stanum properties, a Stanum property being one set apart for the benefit of a person occupying a particular position (Stani) so long as he occupies that position…….The important point is that the properties being family or Stanum properties the head of the family is entitled only to a life interest in them.

The Ammaraja’s estate used to be managed by the senior Rani (i.e. the oldest female Thampuran) for the time being. H.H The Maharaja while he was Elaya Raja assumed the management of estate at the request of the then Senior Rani and managed it with much skill. He continued the management after he ascended the Musnad. Subsequently the management was assumed by the State Government by a Proclamation while Mr. Cotton was agent to the Governor-General and it is still in the hands of the Government, the Manager of the Estate being under the immediate supervision of the Sarvadhikariakar.

The Sarvadhikariakar in addition to being His Highness’s Private Secretary also looks after private affairs and it will thus be seen that he has considerable influence over the management alike of the Palliyara Muthalpidi properties and of the Amma Raja’s estate.”

One of the principal complaints of the Thampurans was about the large sums of expenditure from the Palliyara Muthalpidi for the benefit of the consort and her children after the Maharaja became ill. One of the Thampurans had information obtained surreptitiously from the Palace Accountant. A copy of the same was included with the note. Irregularities in the management of the Ammaraja’s estate and Sarvadhikariakar managing the same instead the Raja infuriated the Thampurans. They were demanding a thorough audit of the accounts of the Palliyara Muthalpidi for the last few years.

Herbert continued “Another, though less important matter, of which the Thampurans complain is the scant courtesy with which they are treated by the Sarvadhikariakar. The following incident is an example of such treatment.

When His Excellency Lord Irwin was about to visit the State the Elaya Raja requested that in view of the small allowance which he was given, the dresses which he would have to buy would be paid for by the Durbar. His request was sent by my predecessor to the Sarvadhikariakar for being placed before H.H. the Maharaja. The request was refused on the ground that it was contrary to precedent and the refusal was communicated to the Elaya Raja. The Elaya Raja then wrote again to the Dewan stating that H.H.the Maharaja had verbally agreed that the dresses should be provided by the Durbar. My predecessor forwarded this letter also to the Sarvadhikariakar on the 8th of September1929. After several reminders had been received from the Elaya Raja the following letter dated 23rd October 1929 was received from the Sarvadhikariakar:-

“Your kind D.O’s Nos.236-62 and 92/1104 dated 8th September 1929 and 20th October 1929 were duly placed before His Highness the Maharaja along with the letter from His Highness the Elaya Raja’s Palace sent herewith.

I am commanded to inform you that His Highness was greatly surprised tom find the misleading statement in the letter under reference that His Highness sanctioned the Elaya Raja’s request with pleasure when it was verbally made to His Highness in the course of a personal interview. His Highness has only to inform you that the statement is not true and that His Highness could hardly believe that His Highness the Elaya Raja would have permitted such a statement to be made in an official

letter to the Dewan of the State. I am also to add that as already indicated in my letter to you dated 26th August 1929 His Highness is not inclined to consider the requisition favorably and that His Highness did not consider the letter reserved any notice. His Highness hopes that you will agree that it is a mere waste of time for you and His Highness to answer such references especially when it is well known that His Highness’s attitude in any particular matter used to be communicated to you in time. His Highness is afraid that personal interviews are sought to be taken undue advantage of so as to embarrass the Dewan and to place His Highness in a rather awkward and delicate position.

The letter is herewith returned.”

Considering that this is a communication written by the Sarvadhikariakar about His Highness the Maharaja’s heir apparent its tone could hardly be more impertinent. There is not the least likelihood that the Elaya Raja would have stated that His Highness had verbally sanctioned his request if in fact His Highness had not done so. The incident is also an illuminating example of the way in which the Sarvadhikariakar exploits His Highness’s present condition and his own position in the Palace.

I have endeavored in this note to describe the situation created in the State by the present condition of His Highness’s health and the difficulties that arise as a consequence in the transaction of State affairs. I do not think those difficulties are likely to diminish as time goes on: on the contrary as interference from the Palace are increasing there seems every reason to apprehend that administration in future become more and more difficult. Two methods of dealing with this situation now appear to exist. The first is to allow the administration to be carried on, as it was carried on in the past, under the influence of the consort and the Sarvadhikariakar. In that event there is, in my opinion, no possible advantage to be gained by a Dewan appointed from British India at the head of the administration: for his proposals can always be vetoed by the consort and the Sarvadhikariakar, it is evident that his opportunities for improving the administration will be exceedingly limited. The balance of advantage in these circumstances seems to me definitely to lie in the appointment of an indigenous Dewan. For the chances of friction arising on administrative questions between the consort and the Sarvadhikariakar on the one hand and the Dewan on the other would be minimized by such an appointment while the administration itself could in the circumstances lose nothing by it.

The alternative course would be to check the influence of the consort and the Sarvadhikariakar. It was with this aim in view that I suggested the transfer of the

Sarvadhikariakar from his present post. Whether that would in fact have solved the problem it is of course now impossible to say: there was at least the chance of its doing so. But it is doubtful whether, matters having reached the stage which they have now done, it will be worthwhile to go to the trouble of securing the Sarvadhikariakar’s transfer merely for the sake of making the experiment. Assuming that it is desirable to interfere in the matter at all the better course would be definitely to end the part which His Highness’s consort and the Sarvadhikariakar now take in the administration.

One thing is thus clear. The time has now come when a definite decision has to be taken whether on the one hand to allow the consort and the Sarvadhikariakar to continue their interference in the affairs of the State: or, on the other to limit if not to terminate that interference altogether. In the former alternative the balance of advantage is against having a Dewan from outside the State at the head of the administration: for this can only result in friction in administrative matters without any corresponding gain. “

24 Th December 1931 Sd. C. G. Herbert

It was already mentioned that a few documents were enclosed with the note. These are available in the digital file.

On 3rd January 1932 Col Pritchard replies with a copy to the Hon’ble Sir Charles Watson, Political Secretary to the Government of India, New Delhi.

“After discussing the case with Herbert, and especially in view of His Highness’s mental condition I decided to speak to him on the subject and to endeavor to gauge, if possible, to what extent, if any, His Highness would be disturbed in mind if the proposed transfer of the Sarvadhikariakar was effected. Consequently I took an opportunity of calling on His Highness and was accompanied by an Indian assistant in cade the Maharaja failed to comprehend a conversation in English.

I opened the conversation with a few simple remarks regarding the weather, none of which the Maharaja appeared to understand although all were repeated. He made no reply, nor did he ask me any question. Finally he replied in the negative to my question as to whether he had not heard the very heavy rain which fell in the night. I then informed His Highness that the object of my visit was to ascertain casually what his objections were to the Dewan’s proposal about the Sarvadhikariakar. I repeated this twice and as His Highness made no reply.

I had the sentence translated into Malayalam. The Maharaja appeared to have some difficulty in understanding what had been said, but, finally, he replied ‘I have objection’. Asked what exactly his objections were His Highness said ‘He has been here a long time.’ On my enquiring whether there were any other objections the Maharaja replied in the negative. I then unfolded His Highness’s letter of the 18Th September and remarked that I would like to talk to him about it. As he appeared to be quite oblivious of what I was doing I said to him “You remember sending me this letter?” to which he replied ‘No’. I handed it to him and he fixed his gaze on the top edge of the paper, and after some little time, his eyes wandered to the ceiling of the room. Presently he handed the letter back saying ‘read’. I did so slowly and he repeatedly interjected “C.G.Herbert?” and sometimes “Sarvadhi?’. On each occasion I informed His Highness that the letter was not from Herbert, but from himself. I tried His Highness again in Malayalam, and he said that he did not want another Sarvadhikariakar as he would be “new”. I remarked in an aside to my Indian assistant that I would not continue to press the matter and His Highness, who heard, enquired “Will you not press?” to which I replied that I would not go so far at the present. It was his solitary spontaneous flash of intelligence throughout the interview.

It seemed to me to be apparent that the Maharaja had been apprised beforehand of the probability of my visit being in connexion with the Sarvadhikariakar that he had been tutored; that he was mentally incapable of following the line of thought laid down for him, and it required a considerable effort on his part to appreciate at all that he was expected to discuss a matter pertaining to himself, Herbert and the Sarvadhikariakar. Furthermore it was clear that he recollected nothing about the letter of the 18Th September which purported to come from him, and I carried away the strong impression that he would not suffer any disturbance of mind if the Sarvadhikariakar was transferred. I was certainly unable to detect that the prospect of parting company with the Sarvadhikariakar had evoked any mental distress or excitement.

In order to give a further illustration of His Highness’s condition I will describe briefly his behavior at the Durbar which was held in connexion with the presentation of Kharitas from Lord Irvin and the Viceroy. As I shook hands he broke into a guffaw of inane laughter which I must confess was somewhat disconcerting. I tried to enter into the usual brief conversation, but His Highness remained completely dumb until I asked whether he found the climate cooler in Tripunithurai than in Ernakulam. I must mention that we were then sitting in his Palace in Tripunithurai. His Highness turned to me and said “Where is Tripunithurai?”. During the firing of the Vice regal salute His Highness created

some embarrassment by repeatedly calling out “What is the firing for?” and much more when he turned to the heir apparent and asked him whether his wife was present! He didn’t know what to do with my garland and finally his hands had to be raised over my head by the Dewan. When my wife received hers His Highness again emitted a peal of laughter saying in a loud voice “Lady Sahiba”. It was altogether an extremely undignified Darbar.”

Col. Pritchard continues:- “There is , of course, not the slightest doubt that these two people have virtually abrogated to themselves the role of the Ruler, and I consider it now essential for the Government of India to make the decision to which Herbert refers………………He feels that as the Maharaja is precluded by mental defectiveness from transacting State business either by discussion or correspondence; that as the interference of a corrupt consort and her favorite is adverse to the interests of the State, and, it is believed, to the interests of all the male and female members of the Ruling family of whom there are about three hundred, and that the present system of administration is an undesirable sham, which, apart from other obvious considerations, touches his self-respect, remedial action which must necessarily be drastic, should now be taken. I am in complete agreement with his views.”……………Pritchard continues about his predecessor Crosthwaite’s notes after the latter’s interview with the Thampurans and the previous Dewan’s complaint. “In this connexion the Thampuran said certain unpleasant things about the Highness. While His Highness was in full mental vigor, everything went on in an eminently satisfactory manner, that His Highness the Maharaja was the kindest of masters, that he was very much interested in the members of the Ruling family, that His Highness by reason of old age and ill-health was not able to judge for himself that he was being influenced by others and that what was really taking place was not His Highness’s judgment, but the judgment of others. The Thampuran went on to the length of saying that His Highness was just like a child.”

“In a letter addressed to Cater in December 1929 the Thampurans wrote that, however since their respect and reverence for His Highness’s person was, they felt compelled to complain as they knew that things which were done in His Highness’s name were done by others and that, so far as they knew the Maharaja had practically ceased to function, and that his powers and authority were being usurped by others. Finally they prayed to be freed from a rule by people other than the legitimate Ruler.

The Thampurans are undoubtedly convinced ( and so is Herbert) that the Consort and Sarvadhikariakar are looting the Palliyara Muthalpidi properties, and, as they

are precluded from filing a suit against the Karanavan or manager because he is the Ruler, they very naturally claim that if Government consider it expedient to permit a mentally defective Ruler to retain his powers then it is for the Government to devise some way of protecting them from being robbed.

I may mention here that if Herbert severed his connexion with the State it would be nothing short of a calamity. His good Judgment, ability, industry and sympathy have made a very great impression on the vast majority of the people of Cochin who undoubtedly have complete confidence in him. Where he to leave UI do not imagine that we would find another suitable European I.C.S. Officer to assume charge of an appointment which Herbert’s conscience and self-respect had induced him to vacate.

Herbert has suggested the following courses of action:-

(a) To insist on the Sarvadhikariakar’s transfer.

(b) To act as at(a), and, in addition, to request His Highness not to interfere in administrative matters and to warn him if he did so, the advisability of appointing a Regent would be considered.

(c) To appoint the Elaya Raja as Regent, and to entrust him with the management of the Palliyara Muthalpidi properties.”

Several interesting facets of information could be noted after reviewing the communications between Herbert and Pritchard.

1. Palace accounts indicated every year, from 1918 onwards 25,000 to 35,000 rupees withdrawn from the Palliyara Muthalpidi until 1929 for various reasons.

2. Vellikulangara and Mattathur of forest lands was given to the Palliyara Muthalpidi from the Government during the X-Raja’s time. These lands were leased to the Consort for RS 200/- and cutting the trees fetched Rs 17,000, but nothing was put back in the Muthalpidi.

3. Maharaja’s own Palace when he was first Prince was gifted to the Consort. But she sold it to the Palliyara Muthalpidi for Rs 13,000/- but was assigned as pattom tenure for Rs200/-

4. Few irregularities in dealing with Ammaraja’s estate also has been listed.

5. There was a plan to move the Maharaja’s College from Ernakulam to Ramavarmapuram near Thrissur.

After receiving the letter send by Pritchard a telegram from Polindia arrived on 29/1/1932 “ H.E. the Viceroy directs that you should arrange to have H.H. the

Maharaja of Cochin examined at once by a European mental expert with a view to ascertaining his mental condition and capacity to rule.

Agrees that Doctor Somervell should if possible be associated with the mental expert in this examination.”

Dr Somervell agreed to be of help. Major A.C.A. Smith, Superintendent of the mental hospital of Yeravada, Bombay was to examine the Highness in Madras. But on 25Th March 1932 His Highness Sir Sri Rama Varma G.C.I.E., Maharaja of Cochin died at 7.45 A.M. at Cochin House, Madras.